Connections: The Willow & the Mountain

(This work was recently featured in the 1 January 2022 episode of Artist’s Books Unshelved, presented by Catherine Alice Michaelis, the Asst. Director of the Cynthia Sears Collection at the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art.)

For the 2021 Science Stories Project at The University of Puget Sound…

…I signed on to create an artist book about Sitka willow trees inside the Mt. St. Helens Volcanic Monument. I’d never seen a Sitka willow, but I imagined something from a scene in Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows. Nothing so twee as Rat and Badger boating along the river, but my imaginings definitely contained bucolic scenes featuring fountains of graceful leafy tendrils hovering above the water’s edge.

I suppose this exposes the embarrassing limits of my botanical knowledge at that time. I’ve since learned there are 400 varieties of willow tree – with only a small portion of them the fountaining tendril types.

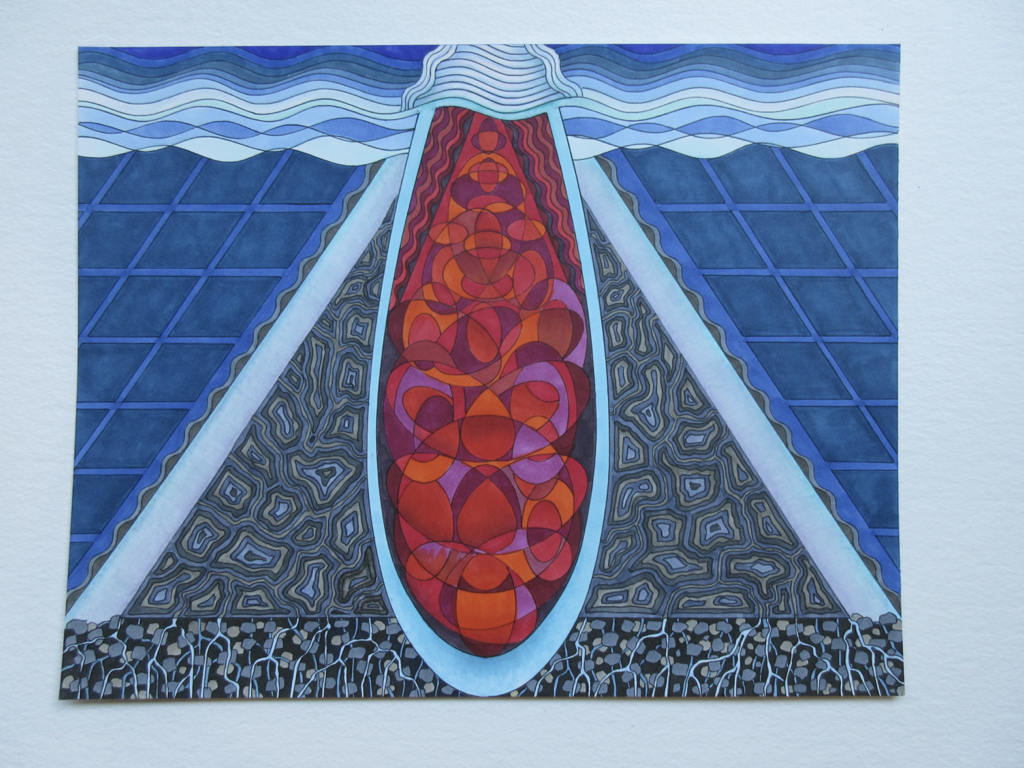

Generally, when I start an artist book project I first look for an linchpin image.

I use this image to set the tone for the book. My second consideration is to settle on the kinetics – how the book’s structure supports the flow of the story I’m telling.

Because of pandemic travel restrictions I was forced to rely entirely on photo sources and written documents instead of visiting the study area in person. Not my ideal way of working.

Downloading research information from my science advisor, Carri LeRoy, I began reading, highlighter in hand. By the time I finished the document some third of the pages are underlined, interlaced with multitudes of scribbled question marks.

I studied photos from her field studies, and discovered something I wasn’t expecting.

The site on the Mt. St. Helens pumice plain looks like scrubland instead of the forested streams I’d imagined.

More to the point, my protagonist, the Sitka willow, is shrub-like in appearance, and not one of the noble trees I’d expected.

Before taking on this project I’d read Peter Wohlleben’s book, Hidden Life of Trees. I thought my book would delve into the mycelium, hyphae, crown shyness, and mycorrhizae networks I’d just learned about. But the willow trees on Mt. St. Helens inhabit a newly formed riparian ecosystem, completely different from the European forests that Wohlleben wrote about. I had to re-imagine my initial concepts and dig deep into research.

I read books about volcanos, stream ecology, Passenger Pigeons (the other subject I considered for an artist book), the Columbia River ecology, the history of Mt. St. Helens, and eyewitness accounts of the eruption. I watched documentaries – lots of documentaries. Many of them about subjects only on the periphery of my topic, like Pompeii, undersea archaeology, the Amazon rainforest, space exploration, and worldwide interconnected ecological systems.

I started to see connections everywhere.

And I realized that my story is larger than one plant. It’s about the mountain and how she’s building new ecosystems upon the scar tissue of the 1980 eruption. But my story is also about connections, resiliency, fresh starts and healing.

To tell this story, I structured my book in two sections—the before (eruption) and the after (colonization of the pumice plain). When I began painting, I knew I didn’t want to do anything literal.

The 1980 eruption is the most documented volcanic event in the world. There are hundreds of brilliant photos from every angle imaginable. I felt no need to duplicate those images. I’ve focused instead on paintings that convey the movement and structure of the events unfolding.

I commissioned handmade papers to add a tactile dimension alongside the text of the story.

Because of travel restrictions, I had to rely on plants I could harvest close to home. I collected and dried suitable stand-ins for wildflowers growing on Mt. St. Helens, then mailed them to my friend, Marilyn, in Los Altos, CA to include in our paper. Her husband, Neil, generously donated his sample of Mt. St. Helens ash collected after the eruption.

My goal with the handmade papers was to bring in the sense of “aliveness” I feel plants always imbue, hoping to soften the hardness that data – facts, numbers, weights and measures – can often lend to text. But I also wanted to avoid relying only on a series of papers with inclusions. Marilyn suggested different papermaking techniques we could use which would say something beyond mere artifact about each topic in the book.

My daughter, Kat, helped me choose a structure.

We collaborated to design a presentation that supports the way I want my paintings, handmade papers, and text to interact. She built mock-ups for us to consider and refined our final choice. Then she had the laborious task of constructing all those grand ideas into a tangible object.

So, from the most basic level on up, this entire project is a study in connections.

Not just between the willow and her relationship with the mountain, but with the materials used to create the story and all the people who added to it. I am most grateful to everyone who helped make this book a reality.